From the Alps to the Pulpit: Olivétan, Waldensians, and the French Bible

- 7 minutes read - 1294 wordsWilliam Tyndale is perhaps the most famous Bible translator in the English-speaking world, but the francosphere (encompassing France, Belgium, Switzerland, and much of Africa) has its own pioneer translator. Pierre Robert Olivétan brought the Hebrew Masoretic Old Testament and Erasmus’ Greek New Testament to French—the first from the original languages. La Bible d’Olivétan shaped French-speaking Protestant identity and laid the groundwork for the Reformation’s spread in France and beyond.

Before Olivétan, the Holy Scriptures were restricted to the clergy and academia. In the Occitan-speaking south of France, the Waldensian barbes (itinerant pastors) had been preaching from their Occitan translation for over three hundred years, but in the langue d’oïl north, hearing the Bible in the people’s tongue was nearly impossible. Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (alias Jacob Faber) was the first to produce a French Bible, but it was not accepted by the early Reformers due to its source text being Jerome’s Latin Vulgate.

The Cousins

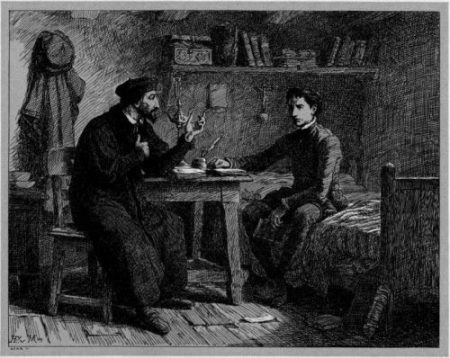

Pierre Robert Olivétan was born in Noyon around 15051. Little is known about his early life, but he was likely a cousin of John Calvin, the famous French Reformer. As young men, both Olivétan and Calvin left for Orléans, where they would study alongside William Farel. Theodore Beza, Calvin’s successor in Geneva, stated that it was Olivétan who introduced Calvin to Martin Luther’s groundbreaking Reformation ideals.

John Calvin and Pierre Robert Olivétan

Threatened by the Orléans clergy, Olivétan fled to Strasbourg in 1528 and studied with another renowned Reformer, Martin Bucer. A year later in Geneva, he joined William Farel and was tasked with teaching the Protestant faith in Neuchâtel, in what is now western Switzerland.

Waldensians Join the Reformation

In 1532, 250 kilometers south of Neuchâtel, dozens of Waldensian lay preachers and families gathered in a narrow valley in the Piedmontese Alps to meet with representatives of the Protestant Reformation, most notably William Farel. The discussions lasted for six days and resulted in the majority of Alpine Waldensians aligning themselves with the Protestant Reformation. However, an often overshadowed outcome of the meeting was that the Waldensian barbes and laity agreed to finance a translation of the Bible from the original languages into French.

Few details have survived about how this decision was made. There is little surprise that the Waldensians would agree to this, seeing they were accustomed to having the Scriptures in their vernacular, yet it seems they did not possess the necessary knowledge of Hebrew and Greek. None would doubt their dedication to the cause; Waldensian families collected 500 gold ecus2 to sponsor the work, an immense sum equivalent to the salary earned by a skilled worker in twenty years3. Farel, meanwhile, had a friend back in Neuchâtel whom he knew could perform this monumental work.

The Work of Translation

On being tasked with the translation, Olivétan traveled to the Waldensian valleys deep in the Cottian Alps4. There he produced a French Bible from the Masoretic Hebrew Old Testament and the third edition of Erasmus’ Greek New Testament (which in later editions would be called the Textus Receptus). For three years, Olivétan lived and worshiped among the Christians who had been defying the pope centuries before Luther.

Little is known about those few years Olivétan spent translating the Bible in the Alps5. The Waldensians there certainly would not have had the resources for the French language, nor of the ancient source languages from which the Bible was translated. The aim was a French Bible, and Olivétan could have just as easily performed his work in Neuchâtel, or if it was seclusion he sought, there were Alpine abodes much closer to his home. The Waldensians had provided all the funds for the translation and printing, so perhaps Farel, Olivétan, and the other French Reformers had wanted to show their appreciation to the Waldensians. But was there more to it? Having preserved and copied the Scriptures in their own vernacular for generations, perhaps the Waldensians possessed a simple biblical understanding that the scholars in Geneva, Neuchâtel, and Basel could not match.

Olivétan finished the translation in 1535. One translation choice of note was his use of “the Eternal” (l’Éternel) to translate the tetragrammaton (יהוה), though he did use Jéhovah in a few places. When Olivétan returned to Neuchâtel, the Bible was typeset and printed by Pierre de Vingle, and multiple prefaces were written for it, one from a young John Calvin and another by Olivètan himself. For the first time, French-speaking Europe could read the whole Bible in the language of the commoner.

Olivétan’s Legacy

As a commercial venture, Olivétan’s translation was a “complete failure”6. Likely due to it being in French instead of their native Occitan, the Waldensians did not make it their standard Bible; in addition, they had already sacrificed greatly, so few were willing to pay yet another sum for the bulky, printed Olivétan volume. Small, hand-copied booklets had been the standard of their itinerant preachers for centuries, not massive folios printed in Gothic script. And old traditions pass slowly.

The King of France quickly banned it; anyone caught with a copy risked arrest, exile, or worse. However, as the Tyndale Bible had been for English readers ten years earlier, the 1535 Bible d’Olivétan became the foundation of French translations. Olivétan’s style and word choices shape the theological vocabulary of French Protestants even to this day7. His work was the basis of John Calvin’s Bible de Genève of 1560 (not to be confused with the English Geneva Bible, coincidentally published in Geneva the same year), Beza’s 1588 revision, and later the popular Osterwald revision of 1744.

Though often overshadowed by more prominent Reformers, Pierre Robert Olivétan played a pivotal role in shaping the religious landscape of the francophone world. His 1535 Bible was more than a literary achievement: it gave the Scriptures to French-speaking people in the language of their hearts. It bridged the chasm between the learned and the laity, between the pulpit and the pew. His translation gave voice to a Reformation that was not merely theological but pastoral, empowering believers across France, Switzerland, and beyond. The Waldensians had long held God’s Word in the secluded valleys of the Alps, but Olivétan helped carry it to the masses of western Europe. His legacy endures not in fame or fortune, but in the faith of countless readers who first encountered the Gospel in their own tongue because one man dared to translate the Word of God for the people.

The Preface

Pierre Robert Olivétan didn’t just translate the Bible—he introduced it with a powerful, deeply personal preface that defends the necessity of Scripture in the common tongue. While Olivétan does not name the Waldensians directly (likely for political or protective reasons), the preface functions as a veiled acknowledgment and celebration of them. It is “to the Waldensians” in everything but name. You can read the full English translation here: English Translation of the Preface to the Bible d’Olivétan (1535).

Curious what 15th-century French in Gothic script looks like? You can view the original scans of the 1535 Olivétan Bible here: The Olivétan Bible (French, 1535).

-

Brian G. Armstrong, “Pierre Robert Olivétan,” Encyclopedia of the Reformed Faith, ed. Donald K. McKim and David F. Wright (Presbyterian Publishing Corporation, 1992), 23. ↩︎

-

Gabriel Audisio, Preachers by Night: the Waldensian Barbes, 15th–16th Centuries (Brill, 2007), 219. ↩︎

-

J. -F. Gilmont, “La fabrication et la vente de la bible d’Olivétan,” Musée neuchâtelois : recueil d’histoire nationale et d’archéologie Musée Neuchâtelois, 3e série, v. 22 (1985), 213–214. ↩︎

-

Frans Van Stam, “Olivétan, not Calvin the author of A tous amateurs, a preface to the oldest French protestant Bible,” Calvin – Saint or Sinner, ed. Herman J. Selderhuis (Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 67. ↩︎

-

Audisio, Preachers by Night, 217. ↩︎

-

Audisio, Preachers by Night, 222. ↩︎

-

E. G. Léonard, Histoire Générale du Protestantisme, vol. 1. (PUF, 1961): 242–243. ↩︎